A Mid-Winter Dispatch

January 4-10, 2026

This is turning into a winter that everyone is talking about, and not necessarily in a good way. We've only had a few sprinkles of snow in weeks, and the forecast for the next three days is rain and freezing rain (with a chance of snow), followed by another round of sunny days.

Week in Review

I'm not sure if much of anything happened this week. There haven't been many posts on the Facebook group, and I've noticed almost no activity on my walks. Perhaps the only change of note is that the great horned owls have started hooting through the night as part of their courtship displays.

The owls are almost certainly spending more time at their nests in preparation for egg-laying, and today I noticed that our local pair of bald eagles is sitting on branches next to their nest as well. It's definitely too early for eagles to begin nesting because there's not enough food for their babies, but great horned owls are famous for laying eggs in late January or February so they can get a jump on the new year.

Although animal activity seems at a low ebb, you'll still run into an occasional flock of small birds. These flocks almost always contain some noisy and hyperactive chickadees and red-breasted nuthatches, along with other birds that appreciate their company. Since there's no need to establish and defend territories in the winter, small birds find safety in numbers by hanging out together.

A Celebration of Shrub-Steppe

Since we're deep in the depths of winter and not getting outside to ski, I thought it would be fun to highlight one of the features that make the Methow Valley such a special place.

Except for a short window in spring when flowers are in full bloom, most people take the valley's shrub-steppe habitats for granted. In fact, these habitats are usually treated as little more than a dry, shrubby backdrop that elicits scorn and displeasure.

It's easy to overlook the fact that the shrub-steppe is actually one of Washington's most diverse and important ecosystems, providing homes for an astonishing range of species, including over 200 species of birds, 30 species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, countless insects, and a phenomenal number of flowers.

These habitats are home to shrubs like bitterbrush, big sagebrush, and rabbitbrush, and steppe (=grass) species such as bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue, and Sandberg bluegrass. Openings between shrubs are filled with countless flowers like balsamroot, silky lupine, yellow bells, and mariposa lily, while the ground is coated with a fragile cryptobiotic crust of algae, fungi, and bacteria that fixes nutrients and stabilizes the soil.

Despite the ecological significance of the shrub-steppe, only 20% of this habitat remains in Washington, and much of the remaining acreage is highly fragmented or degraded by invasive weeds and human activity.

This is also true in the Methow Valley, where we have a significant and unique subset of Washington's last remaining shrub-steppe habitats. Sadly, there's no larger vision or strategy for recognizing and honoring these habitats in the Methow Valley, and we're losing more and more of this precious resource every year.

This matters because shrub-steppe habitats take a very, very long time to recover—and may never recover—from disturbance. Bitterbrush, for example, lives over 100 years and struggles to grow back once it's cut. Every disturbance creates a rip in the ecological fabric, which is quickly taken over by cheatgrass, tumbleweed, knapweed, and other highly invasive weeds that are almost impossible to eradicate.

We have an opportunity to learn about and recognize the value of this habitat together. Unfortunately, much of the damage to shrub-steppe happens when well-meaning homeowners chip away at small patches because they think it's a nuisance or fire hazard.

When spring returns to the valley and flowers start blooming again, pay extra attention to the shrub-steppe this year and notice how vibrant and alive these places are.

Is there more we can do to protect these unique habitats?

Confluence Gallery Showing

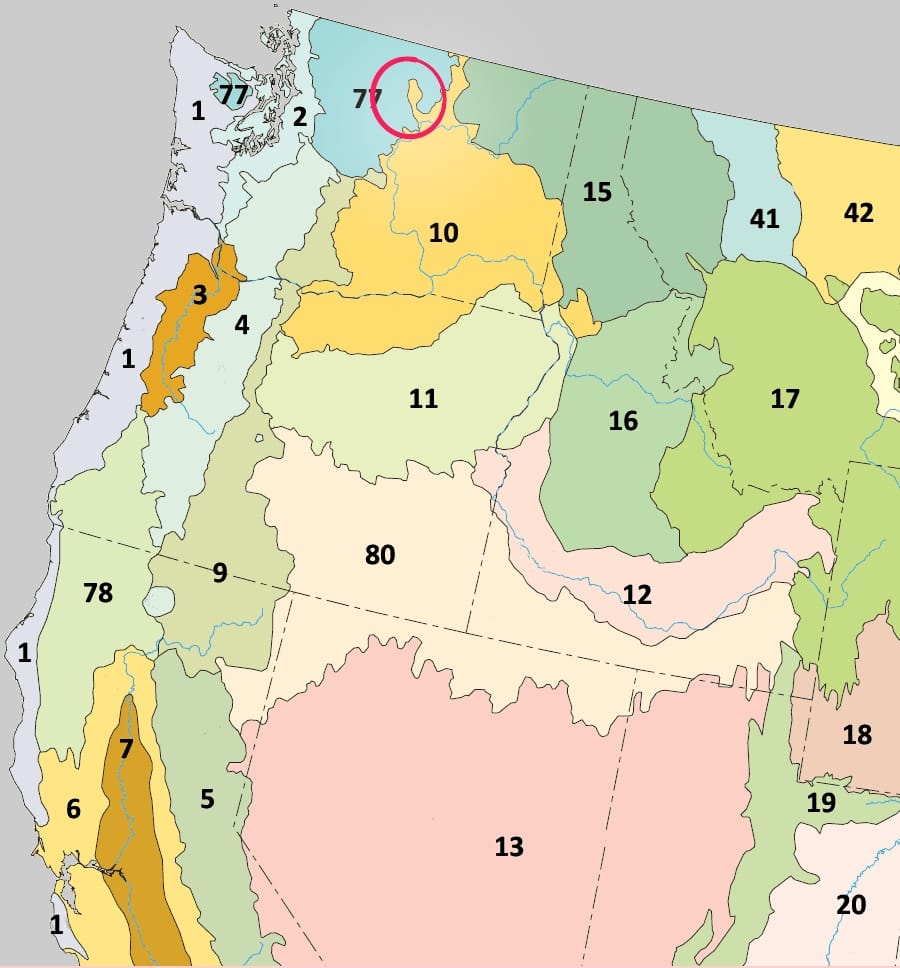

Mark your calendars for a special showing of Shaped by Ice: Altered Ecosystems at the Confluence Gallery from January 13 - February 21, with an opening reception on January 17th, 5:00-7:00 pm.

This exhibit features artists who have worked with and been inspired by the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project, which has been documenting glaciers in the North Cascades for 42 years. See the work of Jill Pelto, Cait Quirk, Emma Mary Murray, Danielle Schlunegger-Warner, Cal Waichler, Claire Seaman, Rose McAdoo, and Margaret Kingston, and learn more about our local glaciers.