July 20-26, 2025

Mid-summer sightings to inspire you

After a brief but welcome dose of rain, the week settled into a pattern of mostly warm and sunny days.

Week in Review

The highlight this week was an extended overnight rain early in the week. It wasn't enough to soak the ground, or alleviate the overall dryness, but the rain smelled (and felt!) fantastic and it brought out some fun critters, including tiger salamanders and spadefoot toads (covered in the Observation of the Week below).

While searching for amphibians during the rain, I was astonished to find an extremely active rattlesnake. Although the ground was wet and the temperature was 56 degrees, this snake was moving so fast that, between spotting it and digging out my camera, I had trouble finding it again. It coiled up briefly while I took a photo but never rattled or threatened me. I'm used to seeing rattlesnakes on hot days when they're mostly sedentary or slow-moving, so seeing one being so active was like seeing a different creature.

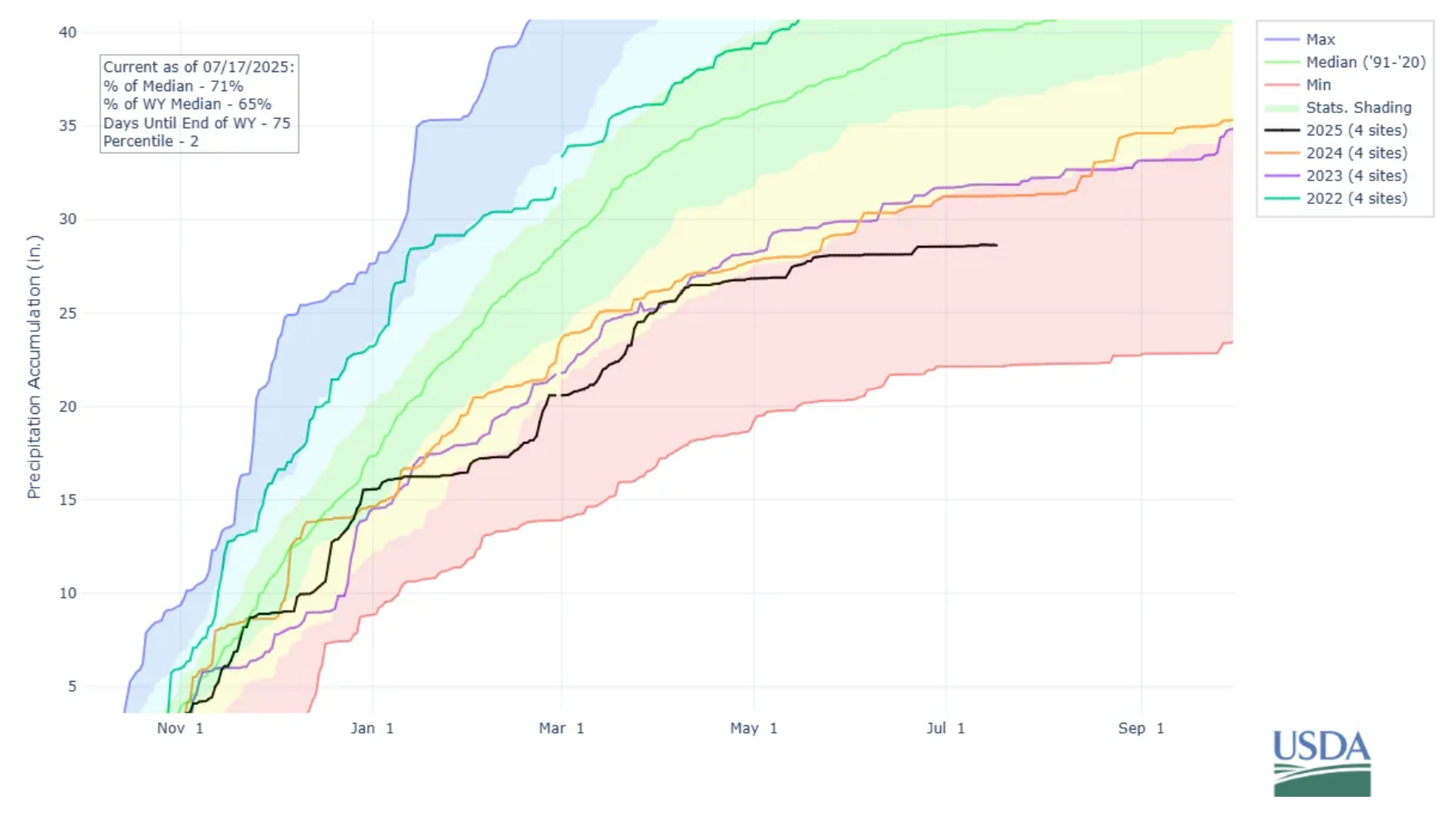

Despite the rain, it's worth noting that we're still in an extreme drought and you can see the impacts of this on the plants and rivers all around us. In their recent newsletter, the Methow Valley Citizen's Council highlighted that rainfall this year is currently 12 inches below normal and the fourth lowest in 131 years. It's spooky, and from what I've been reading about long-term forecasts for the western United States, this drought could last a very, very long time.

Another stress that plants face, especially in such dry conditions, are episodic insect outbreaks. In the Nature Notes newsletter a few weeks ago, we mentioned the extensive outbreak of spruce budworm around Rainy Pass. I don't know that I've ever seen a spruce budworm so it prompted me to take a closer look.

Spruce budworm damage and caterpillars. Photos by David Lukas

Speaking of conifers, this is also the time of year when it's fun to start paying attention to cones. I keep thinking that I've learned to identify all the cones we see on the ground, but every summer I find myself looking up and practicing pinpointing which cones go with which trees.

It's the season for cones. For example, Pacific silver fir (left), mountain hemlock (middle), and subalpine larch (right). Photos by David Lukas

While summer wildflowers are past their peak, you'll still encounter a wonderful variety of flowers on any mountain hike. The most common flowers in the deep forest are foamflower and ones-sided wintergreen, with a few asters in sunny patches and Sitka valerian along seeps.

But as you get higher, and the forest begins to thin, there are an even wider variety of flowers to be found.

This is also the season for huckleberries, though they don't seem to be occurring in great numbers this year. While eating a handful here or there I've been practicing learning how to tell apart our two most common species: black huckleberries of lower elevation conifer forests, and Cascade huckleberries of open subalpine slopes.

Cascade huckleberry (Vaccinium deliciosum) grows as a low dense shrub with white coated berries. This is the huckleberry that turns fiery red in late summer. Photos by David Lukas

Other delights in the high country include watching the antics of this year's baby squirrels and baby chipmunks, and finding unusual late season butterflies.

Observation of the Week: Great Basin Spadefoots

On those rare summer nights when it rains, I like to get out and look for Great Basin spadefoots. These unique toads are expert diggers with horny "spades" on their hind feet that help them dig rapidly into the soil. They spend most of the year buried underground, so they're super hard to find unless it rains during the spring or summer.

Unlike other amphibians, spadefoots have no specific breeding season, they simply emerge in great numbers and gather at breeding ponds whenever it rains. However, because they live in arid or desert areas, where ponds dry up quickly, spadefoot tadpoles turn into toadlets faster than any known frog or toad.

Given the short summers and very cold winters in the Methow Valley, it's likely that most of our spadefoots emerge to breed during early spring rains (compared to summer rains in warmer regions). People occasionally report hearing them calling at their breeding ponds on the Nature Notes Facebook group, but I have yet to hear them calling or see them breeding in the Methow Valley.

Spadefoots can't survive an entire year buried underground, so they eagerly emerge during any rain to search for food, and it's possible that they occasionally emerge on nights when it isn't even raining.

If you go out looking for them, notice that they hop strongly at a slow, ponderous pace and will sit in one spot for long periods of time. They are adorable and fun to watch.