Massive Meltdown

February 8-14, 2026

Whether winter is wrapping up or not, this was a week when much of the valley's snow melted very quickly.

Week in Review

Although the snow cover is rapidly melting from sunlit areas, temperatures continue to drop below freezing at night, so ice is still holding in shaded pockets and forming overnight on still waters. Given the warm weather we've been having, it's a delight to run across these beautiful ice formations when you least expect to see them.

Last week's trend of plants shaking off the snow continued at an accelerated pace this week, and will only pick up steam if these warming temperatures continue over the coming weeks. Look for three plant strategies: plants might hold onto their leaves all winter, drop leaves and regrow new ones, or overwinter as seeds that are now beginning to sprout. There are pros and cons to each strategy, and they all work well.

If there was one big story this week, it would be the abrupt change in bird behavior. People are suddenly noticing that birds are singing everywhere (for example, distant trees are filled with singing house finches even as I type this newsletter).

These lively choruses of birds include a variety of finches, as well as all three of our local nuthatches (pygmy, white-breasted, and red-breasted).

Black-capped chickadees have also become very vocal and lively, and multiple times this week, I heard male chickadees giving the "gargle" calls they use in territorial interactions. Each male has his own unique gargle call, and it's a way of identifying himself to neighboring males ("Hey, I'm Joe and this is my territory."). I wonder if this means that this is the beginning of their breeding season?

Part of the joy of being out this week was noticing how many other birds are active now. These are birds that have been here all winter, but with the change in weather they seem to be more conspicuous and energized. If nothing else, it's a lot more fun to watch birds on a warm, sunny day!

Last Saturday, I mentioned that the weather was so spring-like that it felt like Say's phoebes could show up any day. Well, they showed up two days later! This feels early, but according to Dana Visalli's records, this is well within the range of when we can expect them. Many people watch for Say's phoebes because these early migrants are the heralds of spring in the Methow Valley, and their cheerful calls are a welcome addition!

Observation of the Week: El Niño

This week's "observation of the week" may be hidden from view but it's still been very much in the news recently. Specifically, as this year's oddly mild winter starts to wind down, meteorologists are already noticing that an El Niño event seems to be taking shape in the western Pacific Ocean.

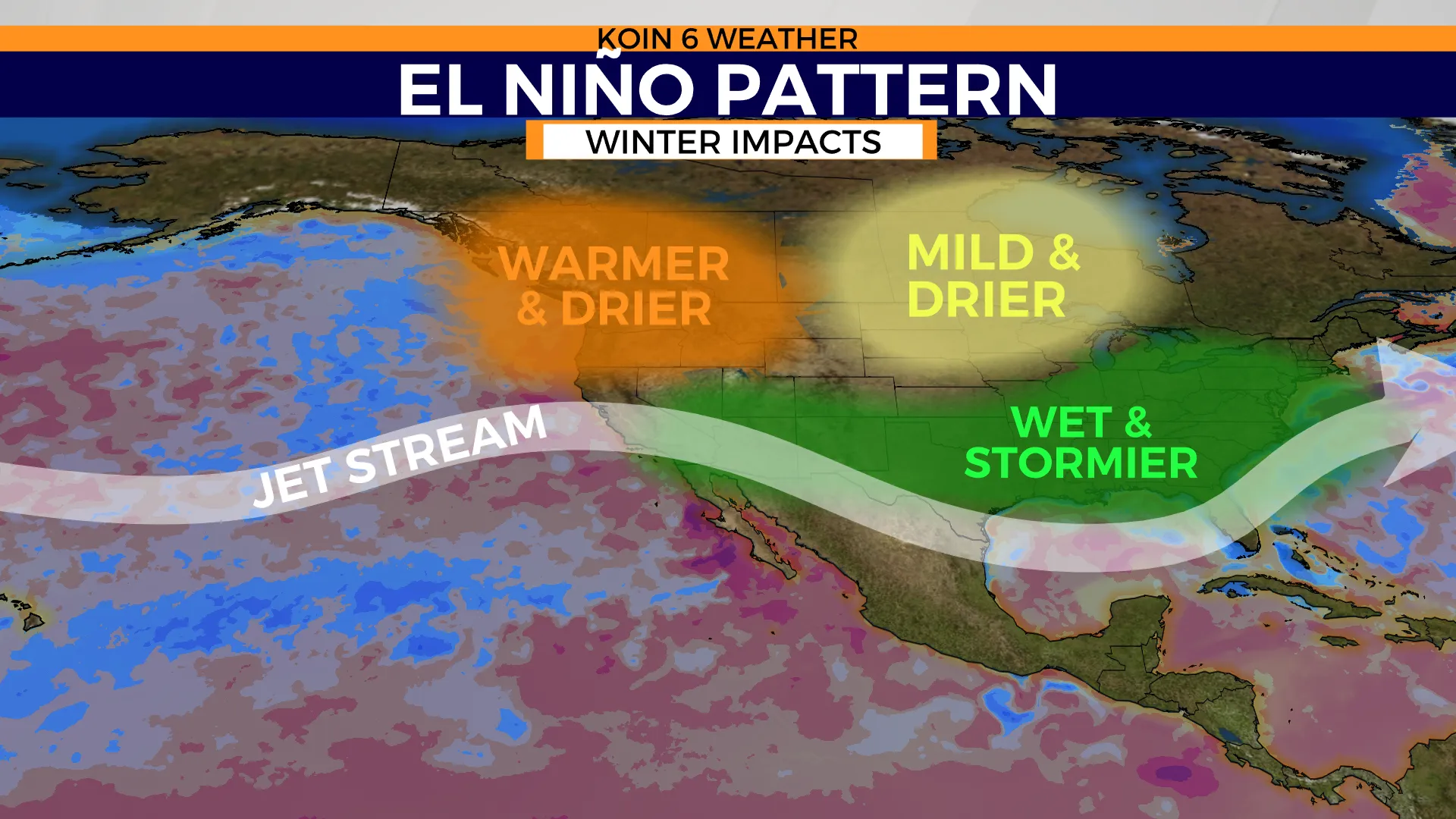

This matters because El Niño events are like slow-moving train wrecks that don't fully arrive until late summer, and then have their greatest impact over the coming winter. Traditionally, if an El Niño event fully develops (and there's no guarantee that it will or won't impact us), it means that next winter could be even warmer and drier than the winter we had this year.

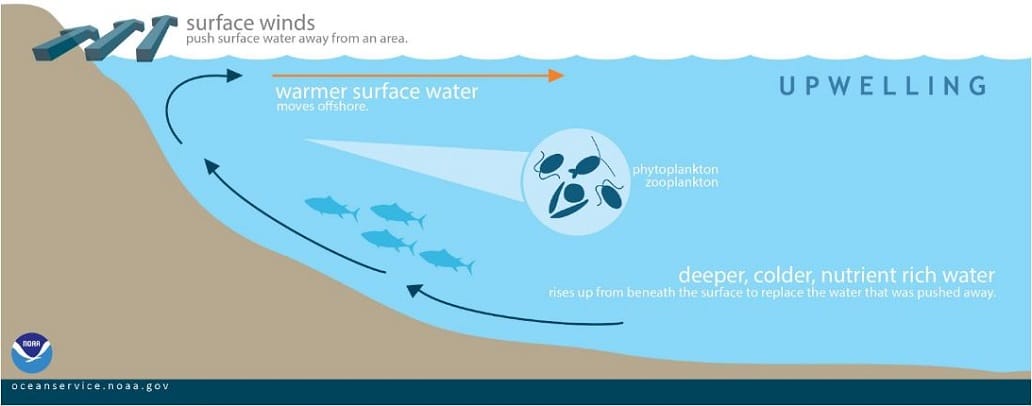

Climate patterns over the Pacific Ocean can be divided into La Niña and El Niño events that can last for years. During a La Niña event, strong trade winds from the east push surface waters westward across the Pacific Ocean, which pulls up cold, deep waters to replace the surface water.

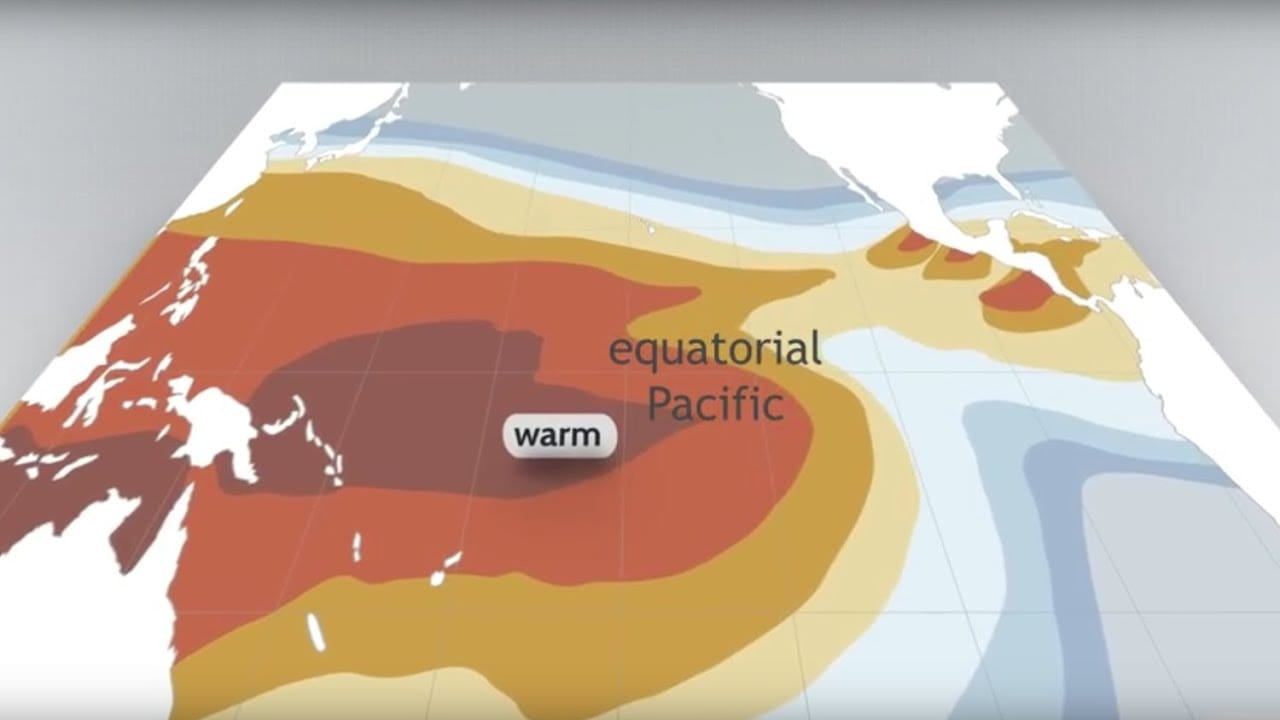

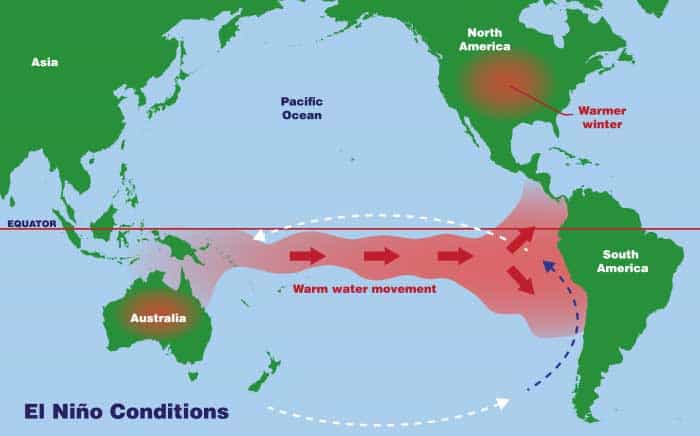

However, during an El Niño event, these trade winds stop pushing westward, and the flow reverses as a giant blob of hot water pushes eastward across the Pacific Ocean until it collides with the western edge of North and South America.

This shift sets off a cascade of climatic consequences, including the fact that warmer air over the ocean rises and reshapes the flow of the jet stream, pushing it northward and insulating the Pacific Northwest from icy polar storms over the coming winter.

Again, there's no way to tell how this year's event will shape up, and we won't know more until mid- to late summer, but it's still something that folks are already watching closely.