Triggered by Light

February 1-7, 2026

Plants and animals use a range of cues to know when spring is coming, but melting snow and warm temperatures in early February might be sending mixed signals.

Week in Review

While clouds and low-lying fog continue to dominate our weather pattern, warm temperatures have led to more melting snow and ice, and for a few brief periods, pools of open water even formed on frozen lakes this week.

Winter is not over, and we might even get a sprinkling of snow in the coming week, but try telling that to the plants and animals that are already responding as if spring is just around the corner.

Folks started hearing treefrogs calling this week, and there was even a report of a saw-whet owl calling in Mazama. A variety of other birds are also becoming more active and conspicuous, and if this trend continues, it feels like we could see the first Say's phoebe of the year any day now.

Plants are also responding to the warming trend (more on this below), with the appearance of some buds and catkins. Unfortunately, emerging too early is very risky because it means that plants are losing their winter-hardiness, which exposes them to damage from late-season frosts.

One of the most interesting developments this week has been the appearance of aquatic insects along the river. They are especially easy to see as they walk across the snowbanks along the water's edge, and I wonder if they're out now because there's an advantage to being active when there are so few insect predators around?

Observation of the Week: New Leaves

One of the most important decisions plants have to make is when to germinate or start growing new leaves in late winter. If plants relied on temperature alone, they might be tricked into sprouting too early every time there's a warm spell. Instead, plants use an internal clock to track daylength.

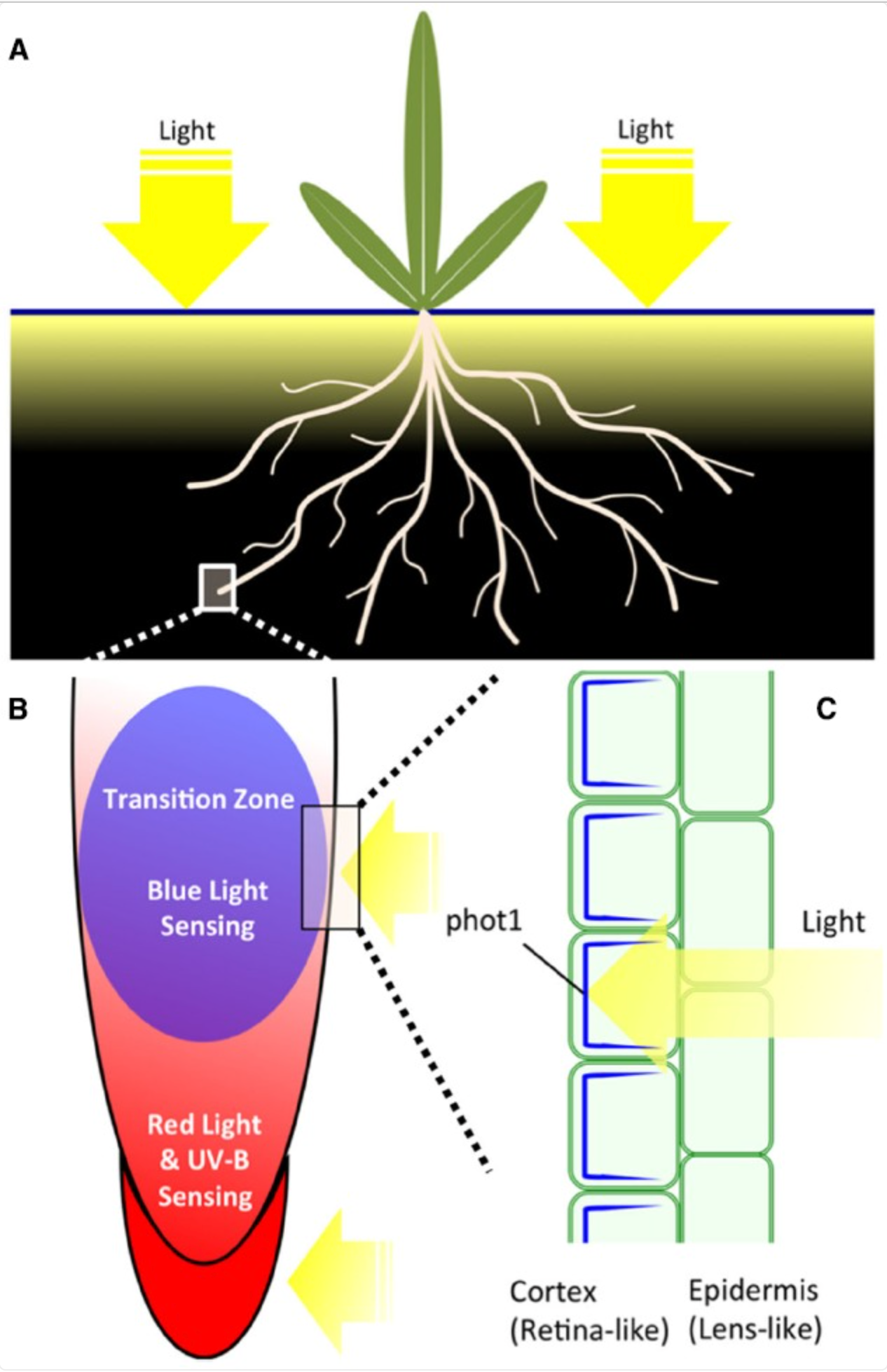

How do plants do that? The simple answer is that plants have light-perceiving proteins called phytochromes, which act as master switches that toggle on and off in response to light and dark. The harder answer is that plants have spent the past 500 million years developing highly complex mechanisms for perceiving and responding to light. These mechanisms are so complex that even though phytochromes are the best-studied proteins in plants, we still barely understand how they work.

Essentially, phytochromes have two states. In the daytime, in the presence of red wavelengths, they switch to a form known as PR, and at night, in the presence of far-red wavelengths, they switch to one known as PFR. The second form is particularly interesting because PFR can further differentiate between the darkness of nighttime and the shade created by other plants, which helps a plant moderate its growth. In fact, this reading of darkness is so important that plants decide to grow based on the length of night rather than the amount of sunlight they perceive.

However, these switches don't directly create the changes we notice in the springtime; instead, they trigger a cascade of biological transformations. Imagine walking into a dark kitchen to make dinner: switching on the light doesn't make dinner, but triggers a sequence of steps that lead to dinner being made.

That said, the relative length of day and night isn't the sole reason why plants start producing new shoots and leaves. If that were the case, they might end up leafing out too early or too late if weather patterns aren't in synchrony with daylength. That's seems to be the case this winter, and it will be interesting to continue watching how plants respond this spring. [Note: This topic is so complex that I think I'll dig deeper into it in a future issue of my Lukas Guides newsletter. Stay tuned if this interests you.]

While walking along the river this week, I kept slipping in clay, so I made a short video about the natural history of clay.